Alzheimer’s disease has plagued one large Colombian family for generations, striking down half of its members in the prime of life. But one member of that family evaded what had seemed would be fate: Despite inheriting the genetic defect that caused her relatives to develop dementia in their 40s, she stayed cognitively healthy into her 70s.

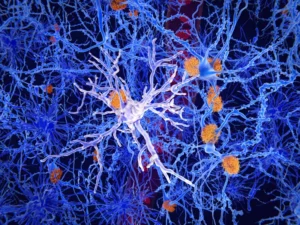

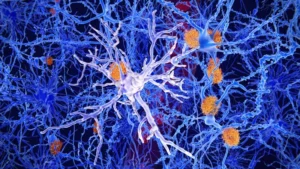

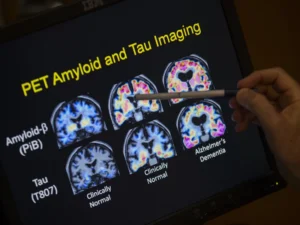

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis now think they know why. A previous study had reported that, unlike her relatives, the woman carried two copies of a rare variant of the APOE gene known as the Christchurch mutation. In this study, researchers used genetically modified mice to show that the Christchurch mutation severs the link between the early phase of Alzheimer’s disease, when a protein called amyloid beta builds up in the brain, and the late phase, when another protein called tau accumulates and cognitive decline sets in. So the woman stayed mentally sharp for decades, even as her brain filled with massive amounts of amyloid. The findings, published Dec. 11 in the journal Cell, suggest a new approach to preventing Alzheimer’s dementia.